This post is a shift from what I usually share on Afraid of What They See. This week, I am facilitating two faculty panels on teaching with AI. Since I taught an entire class on the topic in Fall 2024 and have integrated it into several other courses, I often find myself in these conversations, usually informally, sharing ideas as they come up.

This time, I wanted something I could hand to colleagues looking for concrete examples. One of the biggest challenges in discussing AI in the classroom is that much of the conversation remains abstract and theoretical. People say students should understand the environmental impact, but few discuss what that might look like in an actual lesson plan. There’s very little, Here’s what I tried. Part of the silence, I suspect, comes from discomfort. Many faculty feel uncertain about using AI in academic work, and that uncertainty can shade into shame.

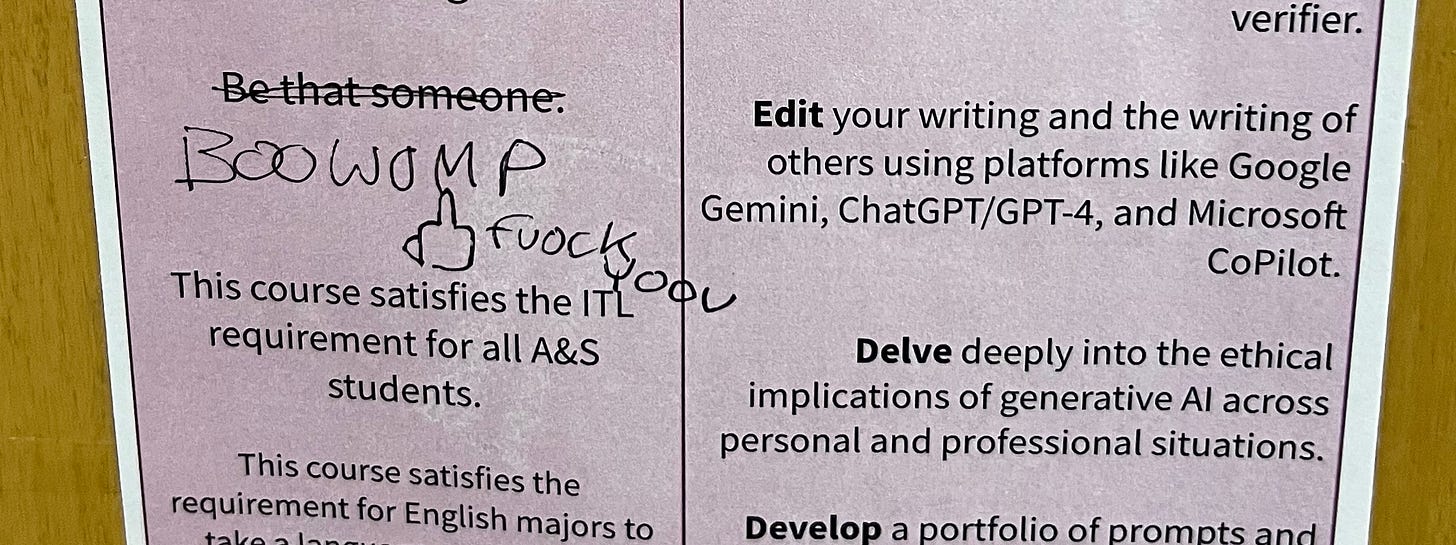

That point was driven home in early August, when I was informed that the flyer for my AI course from last year had been aggressively vandalized.

The news hit hard. I’ve faced misgendering and hate speech in student evaluations since my department closed and I began teaching outside my original disciplines. And when it comes to AI on campus, I’ve often seen conversations shut down instead of opening up. I worry about our campus climate toward these (and other) discussions.

To truly understand AI, you must engage with it. That’s true even if your ultimate goal is to critique or resist it, perhaps especially then. I said much the same in 2005 when I led blogging workshops, and again in 2012 when we considered having students edit Wikipedia. You need to explore the technology to understand what students already know and use.

Early on, many people focused on AI’s speed. But speed is only part of the story, and not the most important part. Used well, AI isn’t about doing more in less time. It often requires slowing down. Yes, it can produce a recipe from a photo of your fridge in seconds, but meaningful academic work with AI is a back-and-forth process. It takes revision, reflection, and deliberate choice.

For context: I am genuinely ambivalent about AI. I’m uneasy with how quickly it’s developing and with its deep entanglement in corporate, neoliberal systems, concerns I’ve carried since Amazon first began tracking purchases to market products back to us, which now seems almost quaint.

And yet, when it works, it’s astonishing. This past year, AI has helped me move forward when I was stuck. Sometimes all I need is to ask for three possible next steps, choose the one that resonates, and combine it with elements from the others. I’m finding that, for me, AI’s greatest strength is not in giving me the answer, but in helping me see where to go next. That’s how I teach it.

Student Perspectives

Last spring, I asked my professional writing students to consider what the university should be doing in response to AI. I’ll explore their ideas in more detail below, but two themes stood out—and they were strikingly consistent.

First, many wanted 24/7 tutoring and spoke positively about tools like NotebookLM and ChatGPT for providing it.

Second, they felt more comfortable asking AI for help than approaching some professors. As several put it, AI doesn’t get impatient, act annoyed, or become dismissive. Professors sometimes do.

The perception of AI as a “safe space” demands further attention. It raises important questions about dependency, avoidance, and the kind of responsiveness we expect from each other in both academic and public life.

Two Ironies

I run device-free classrooms in my 100-level courses, but not because of AI. That decision came after years of observing laptops being opened without the assigned readings on screen and without students taking notes. It simply wasn’t working. In my 300-level course this semester, Mondays are also device-free for the same reason: to encourage focus and deeper engagement.

I also use bluebooks for handwritten journals and index cards for entry and exit tickets, not as a reaction to AI, but because they’ve long been part of expressivist pedagogy, which shaped my early training. In-class, timed writing has always been a central feature of my teaching. What troubles me is how bluebooks are now often framed as tools of resistance and surveillance rather than tools of expression. In my classrooms, they remain the latter.

Addressing the Problems

I don’t know exactly why the antagonistic graffiti in the photograph above was written, or what message it was meant to send to me—or to anyone else who saw it (I hope they saw my em-dash!). Perhaps the writer assumed I celebrate AI and ignore its problems. In my experience, many people agree that students should learn about the issues, yet are unwilling to teach them.

I do teach them. Students have informed me that they were previously unaware of these issues until they encountered them in my class. Those who come in with prior knowledge often hold misinformation or half-formed ideas. They are aware of concerns, but they lack the counterarguments and broader context that provide a fuller understanding.

My approach is to help students learn enough to think clearly and speak with confidence. I remind them that they will almost certainly be asked about AI in a job interview, and they should be prepared to explain their perspective regardless of where it falls on the pro/con spectrum.

Copyright and Data. Like every aspect of the AI conversation, there is a history here. Copyright disputes flared when Amazon began offering book previews, and similar battles continued until 2019. Google faced major legal challenges over the creation of Google Books, yet we still routinely send students there for research. This summer, federal courts ruled that using copyrighted material to train AI is legal, though Anthropic still faces trial for allegedly pirating books. In class, I sometimes walk students through the history of online surveillance technologies to show how we arrived at a moment when AI systems can collect vast amounts of personal and cultural data with minimal oversight.

Energy Use. When I introduce AI, I start with the “What do we do with Carl?” small-group exercise, then hold up a bottle of water each time I ask AI to perform a task. I ask students to imagine the amount of water being used to cool the data centers powering the response. It’s a simple gesture, but it often catches them off guard. This summer, Jules White, a leader in AI at Vanderbilt University, argued that the energy required to make a cup of coffee with a Keurig is roughly equal to one hundred AI prompts. Others have compared AI use to driving a car or eating a hamburger. I remain cautious about these kinds of equivalencies, which can oversimplify or distort the scale of the problem. I was recently informed about the “What Uses More?” website, which compares energy usage for various tasks.

Labor Practices and “Enslaved” People. The term “slave” is often misused in conversations about the labor behind AI, and precision matters. My American identity likely shapes my sensitivity to that language, but the need for accuracy is universal.

I’m not claiming moral high ground. I use an iPhone, as do most of my students, and I’m typing this on an iMac. Extractive and colonizing labor systems are embedded in the production of our devices, as well as in the development and training of AI. These working conditions are often invisible and deeply dehumanizing. They are real, they have histories, and if we want students to do more than make vague ethical gestures, we must teach those histories directly.

Bias. Bias is one of the easiest topics to raise when discussing AI, and for good reason. Language itself carries bias, and most AI is trained on internet content that reflects and often amplifies those patterns. (To help students see how bias operates in language more broadly, I sometimes have them work in groups to define the word abortion in a way that both pro-choice and pro-life individuals could agree on. The exercise quickly reveals how difficult true neutrality can be.) With AI, visual stereotypes are often the clearest entry point. Image-generation tools frequently reproduce familiar, problematic assumptions about race, gender, class, and appearance. These concerns are not new. Questions about bias in language go back to Plato and Aristotle, but AI makes them harder to ignore.

Making AI Work

One adaptable strategy for any discipline is to have students reflect on how, or whether, they used AI during an assignment. Choosing not to use it can be as meaningful as active engagement. Some instructors ask students to use AI to generate options, such as five possible thesis statements from an early draft or three potential outlines based on a brainstorming session (which is what I do with my own work). Others have students prompt the AI to “interview” them about their topic to uncover new angles or clarify their thinking. Afterward, students assess how useful the interaction was or wasn’t. This summer, I heard a thoughtful variation: students write a brief paragraph justifying their decision to use or avoid AI. This approach invites discussion and critical thinking without requiring anyone to adopt a particular stance. I will be asking students to do this when they complete the major formal work for my class.

Break projects into smaller units and work with AI one step at a time. This applies to everyone, including students and faculty alike. For AI to be effective, the process has to slow down. From the start, much of the hype has centered on speed. Yes, AI can generate hundreds of words in seconds, but they’re rarely the right words. Stronger, more thoughtful results come from a slower, back-and-forth exchange. If you want students to use AI meaningfully, either break the project into manageable chunks yourself or make identifying those chunks part of the assignment. This approach draws from process pedagogy, which asks students to reflect on how they build toward a final product. For some faculty, that shift in mindset is just as important as the shift in tools.

What I’ve Done

Before the last academic year, I reviewed every part of my syllabus that I could revise (excluding official course descriptions and policies, such as Academic Honesty) and ran each section through Claude. This summer, I repeated the process with ChatGPT, which I began using more consistently after its March update. For each section, I provided context about the course and asked the AI to revise for clarity while maintaining a student-centered perspective. I tend to over-explain, so this served as a useful check. I copied the AI’s suggestions into a separate document, edited them, and then integrated the final version into the syllabus, adjusting the formatting as needed. The changes were rarely dramatic, but they were often effective.

In Fall 2024, I taught three classes.

In ENG 390: Rhetorics of Generative AI, a special topics course, I worked with a small but highly engaged group of students, one of whom is facilitating the student perspectives panel, who completed eight distinct tasks using AI, like planning a trip. Then, they focused on four scenarios related to revising their own writing and that of others. Because AI evolves so rapidly, I would need to redesign the course entirely if I were to teach it again, incorporating flexibility into the structure from the outset. Even so, it was an incredibly productive semester. The students learned a great deal, and so did I.

In USA 145: Poets and Painters, we used AI twice to generate images. First, students created a visual representation of a poem we had read. Later, they generated an image of a main character from the novel we studied. The novel assignment was especially effective because it required students to reread the text closely, pulling out precise adjectives and descriptive details. It also opened the door to a conversation about bias, both in the stereotypical features that appeared in some AI-generated images and in the assumptions we brought to the task.

In FYS 100: The Roots and Routes of EDM, I used AI only to review course materials. Since I had already taught the class several times, I chose not to integrate AI into student assignments.

In Spring 2025, I taught four classes.

In WRT 215W: Introduction to Professional Writing, students wrote individual proposals to the university president or their college dean recommending how the University of Hartford should approach AI integration in undergraduate education. They then worked in randomly assigned groups to create a collaborative presentation on the same topic for the final class. This is where I learned just how much they want the conversational, 24/7 tutor. For this assignment, I asked AI to create two in-class activities. Students reported that one directly helped them with the project, while the other was merely “fine.”

In GS/ENG 155D: Introduction to Women’s Literature, I used AI to generate active learning ideas for teaching Flannery O’Connor and Joyce Carol Oates, since I had not taught their work before. One suggestion—a gallery walk activity—had students categorize quotations from the texts. The AI even supplied the quotations, drawn from the stories I had uploaded, and I verified each one for accuracy. A few students in the class had taken my AI course the previous fall, which made me comfortable enough to share that the idea came from AI. I did not, however, ask students to use AI themselves in this course.

In UISC 190: Medical Humanities, students created a medical ethics case as part of their final collaborative presentation. One element involved presenting their case to a simulated hospital ethics board on Blackboard using the role-playing feature introduced in 2024. The AI-generated responses were adequate but not especially detailed. I am not a strong supporter of Microsoft Copilot, which powers Blackboard’s AI features. In hindsight, I wish I had included an earlier assignment that involved interacting with a historical figure, ideally someone with a well-documented background, so students could engage initially with the AI’s response. Next time, I may use a different platform better suited to this kind of task, or develop a copy-and-paste prompt for ChatGPT. I don’t yet have the skills to create a custom GPT, though I understand it’s possible. Ultimately, students would have benefited from a low-stakes practice activity earlier in the semester, and I should have given more specific guidance for the reflection component of the final assignment.

In CRD 200: Career Preparation for Humanities Majors, I struggled. This was a pass/no-pass course that met for only one hour per week, and from the start, some students made it clear they had no interest in AI. A few even said they opposed any of their tuition being used to support AI tools. I had planned to introduce resources from our career services office, which include AI-driven tools, but the pushback was immediate. When I demonstrated the AI features embedded in Blackboard, hoping to show how widespread these technologies already are, the class disengaged completely. The atmosphere grew tense any time the subject came up. At one point, I shared a job listing seeking someone critical of AI but knowledgeable enough to explain why. I intended it as proof that skeptical perspectives have value. Students, however, felt provoked rather than empowered. I never found a way into the conversation that worked.

What I’m Doing

For Fall 2025, I will be teaching two classes.

In ENG 142: Introduction to American Literature, students will choose a broad theme (such as gender, race, or war) and investigate how it is represented in literature. After completing two one-page responses, I will introduce an assignment that uses AI: a prompt asking the system to generate three possible thesis statements and approaches for a longer paper. Students will then develop their longer paper from this interaction. As part of the reflection, they will explain why they made the choices they did after receiving the AI-generated options. Research continues to show that reflection is essential to any assignment involving AI, and I want students to practice articulating their reasoning. Because NotebookLM is already a popular tool among students and consumes significant energy, I’ve created a shared notebook for each text we are reading. Each notebook contains the standard study documents and an accompanying podcast, which students have told me they use heavily. This way, twenty-five students are not duplicating the same energy-intensive process. The same principle applies to the essay prompt: rather than asking each student to experiment with multiple variations, I will provide a shared prompt to generate thesis approaches. They will then focus their energy on choosing among the options, refining them, and reflecting on their choices, a skill I hope they are also developing in other classes.

In ENG 317W: Creative Nonfiction, students will spend two weeks writing an essay on AI, focusing on either its use or its avoidance. Some may choose to experiment directly with AI, while others may prefer to reflect on time spent offline. The goal is for them to develop theoretically grounded beliefs about their choices. I am considering a role-play activity on Blackboard or a structured prompt on another platform to support the assignment. Throughout the semester, I will point students to examples of how writers have used AI, highlight possibilities I have discovered in my own practice, and share questions I have heard applicants struggle with during job interviews. I aim to show students not only how AI can shape their creative process, but also how to articulate a position on its role in their professional and personal lives.

The Rest of Your Life

You can plan a meal by taking a photo of your fridge (how many years before the fridge orders our groceries to be delivered?). Parents and caregivers are using it to help kids eat food they would not normally eat. My students and I used it to create a story about the benefits of broccoli, featuring Pokémon characters, for parents to share at mealtime with reluctant eaters. People are using it for scheduling. You can use it for trip planning.

What have I done in my daily life?

I have asked AI to create alt-text for images (as I did for the one at the top of this page) and HTML codes for colors I can use as text on images.

I scanned a family document from the 19th century and asked AI to help me decipher what the handwriting said, something that stumped my parents for the entirety of their lives.

I took photos of the buttons on my new refrigerator and asked what certain symbols meant and what settings to use for my needs.

Fashion advice, seriously. I prompted ChatGPT, “Based on what you know about me, what are casual shoes I should consider for daily wear, especially in the classroom?” At the Teaching and Learning Collaborative on campus, I will be wearing option four. You can decide how much they represent “queer edge,” which is one of the adjectives that came up for what AI said I needed.

Final Caveat

Never take anything AI gives you at face value, just as we never took Wikipedia or Google at face value. Treat these systems as what they are: tools shaped by ideology, yet still useful as means to other ends. Keep that focus. We also need to be deliberate about boundaries. Some will be legislative, some pedagogical, and some personal. In each case, the challenge is the same: to remain aware of the systems at work while choosing how to use them and when not to use them at all.