Tethered One: The Things We Saved without Knowing Why

The ordinary artifacts we didn’t mean to save, and what they tell us now.

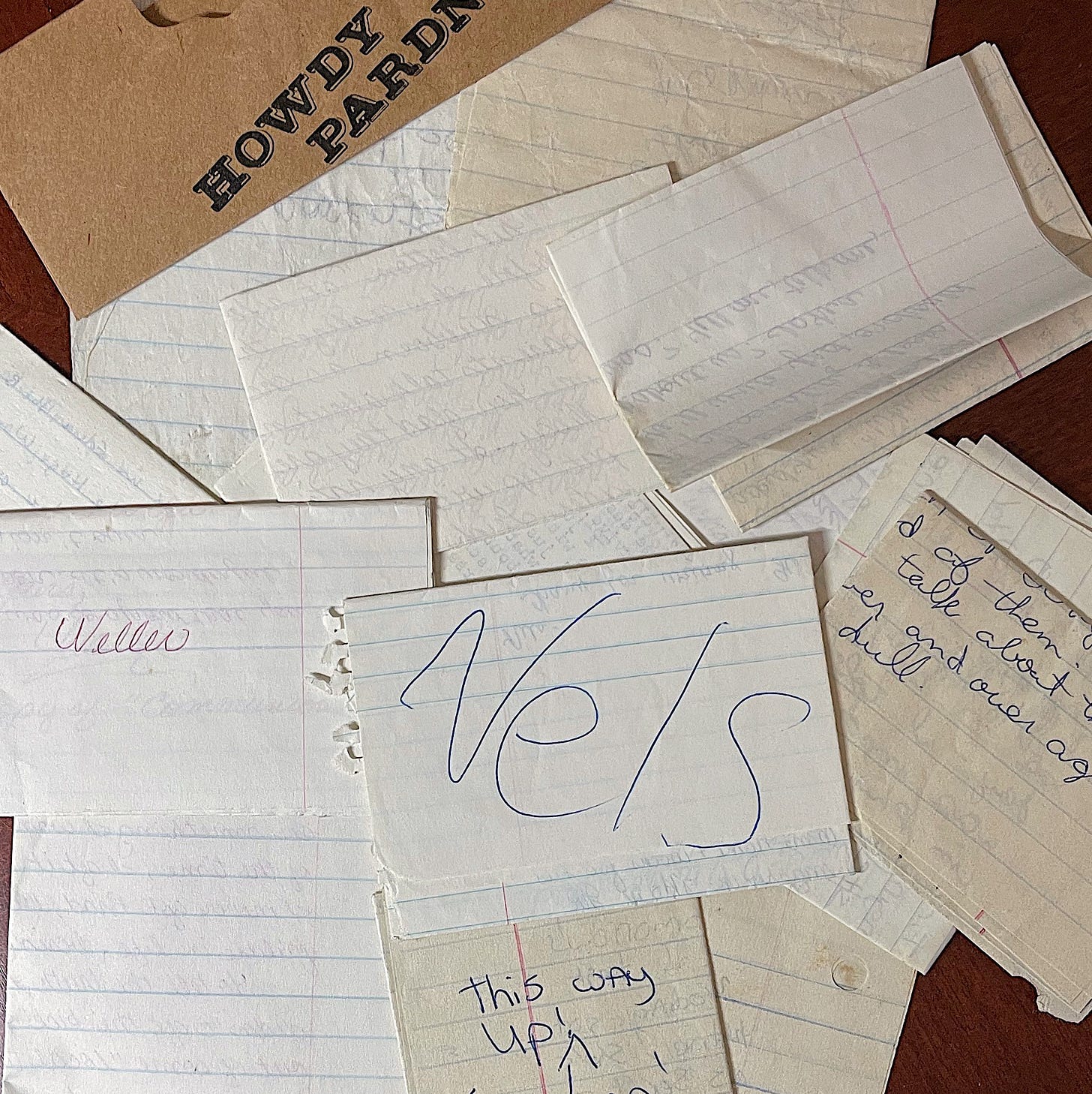

The paper is soft now, worn thin by time and folding. Ink has seeped into the fibers, the edges crimped from being tucked and untucked from the pockets of Trapper Keepers, jeans, and the hidden nooks and crannies of backpacks. Some notes are scrawled fast in pencil; others show careful loops in blue ballpoint, the handwriting of a friend taking their time. I lay them out like artifacts — Nels. Neller. Words written and rewritten by people who knew me before I knew myself.

We passed these notes in the dim fluorescence of high school classrooms, believing they were disposable, transient, as easy to crumple as they were to pass. We didn’t know we were already archiving ourselves. Not formally, not even intentionally, but what survives has its own kind of insistence. These scraps have lasted longer than most of the textbooks we pretended to read. They are anchors to a past both distant and immediate, heavy with laughter and the simplicity of knowing who your friends were before anything had to be explained.

Even before I understood what an archive was, I recognized the urge to preserve, not in a deliberate or curated way, but in the small, unconscious gestures of slipping a note into a pocket instead of throwing it away, or folding a newspaper cartoon carefully into the pages of a spiral notebook.

When I was a teenager, I discovered Sylvia Plath’s journals and Anne Sexton’s letters through interlibrary loan at the county library. I devoured them, astonished at how private fragments — drafts, lists, marginalia — could later become essential documents of a life and art. It made me wonder what might be hidden in the ordinary scraps around me.

I wasn’t consciously trying to build anything. It was instinct, a way to hold onto a feeling, a moment. I didn’t keep everything. What I have now sits easily in boxes and envelopes on shelves in a bedroom closet. The keeping of most scraps happened by accident, yet each became a tether back to myself, the parts of me that changed, and the parts of me that remain indelible.

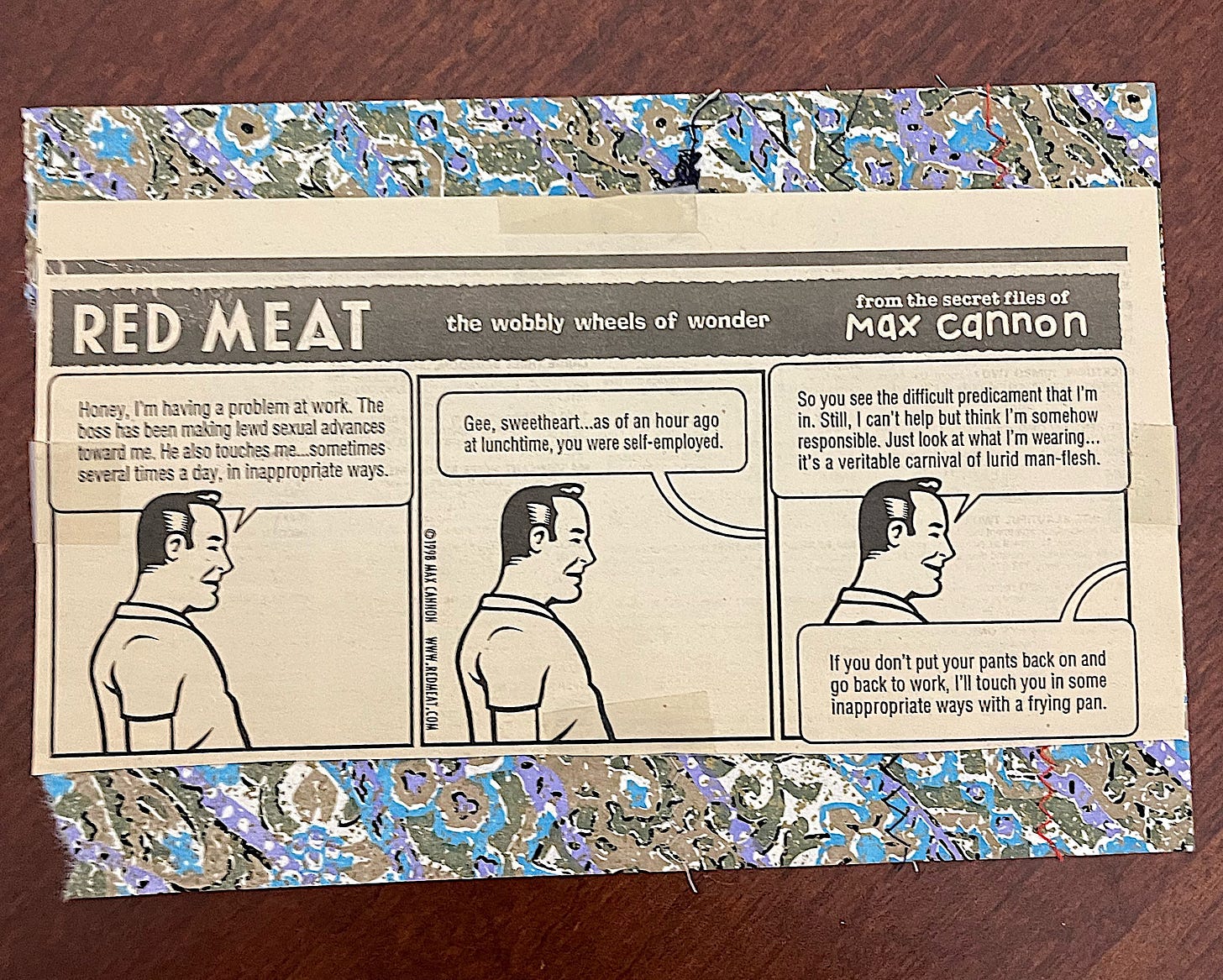

Other fragments — cartoons cut carefully from alternative weeklies, scribbled jokes, strange and small things for walls and bulletin boards — tucked themselves between the notes and newspaper clippings. A yellowed “Red Meat” cartoon by Max Cannon still makes me laugh out loud; the punchline is absurd and perfect, its humor stitched permanently to a particular time and place: a Houston dorm room in a building that no longer exists. It’s an unoriginal joke now, having resurfaced across media for years, but when I first read it as a teenager, I lost my mind. I guffawed.

These were our secret codes, our ways of connecting with others, or saying, I see you without having to explain ourselves. It was also a way to realize someone else’s brain worked like mine, so if I was a freak, I wasn’t the only one. Humor was a way to claim ourselves as distinct from the larger machinery around us: the town, the rules, the slow weight of expectations.

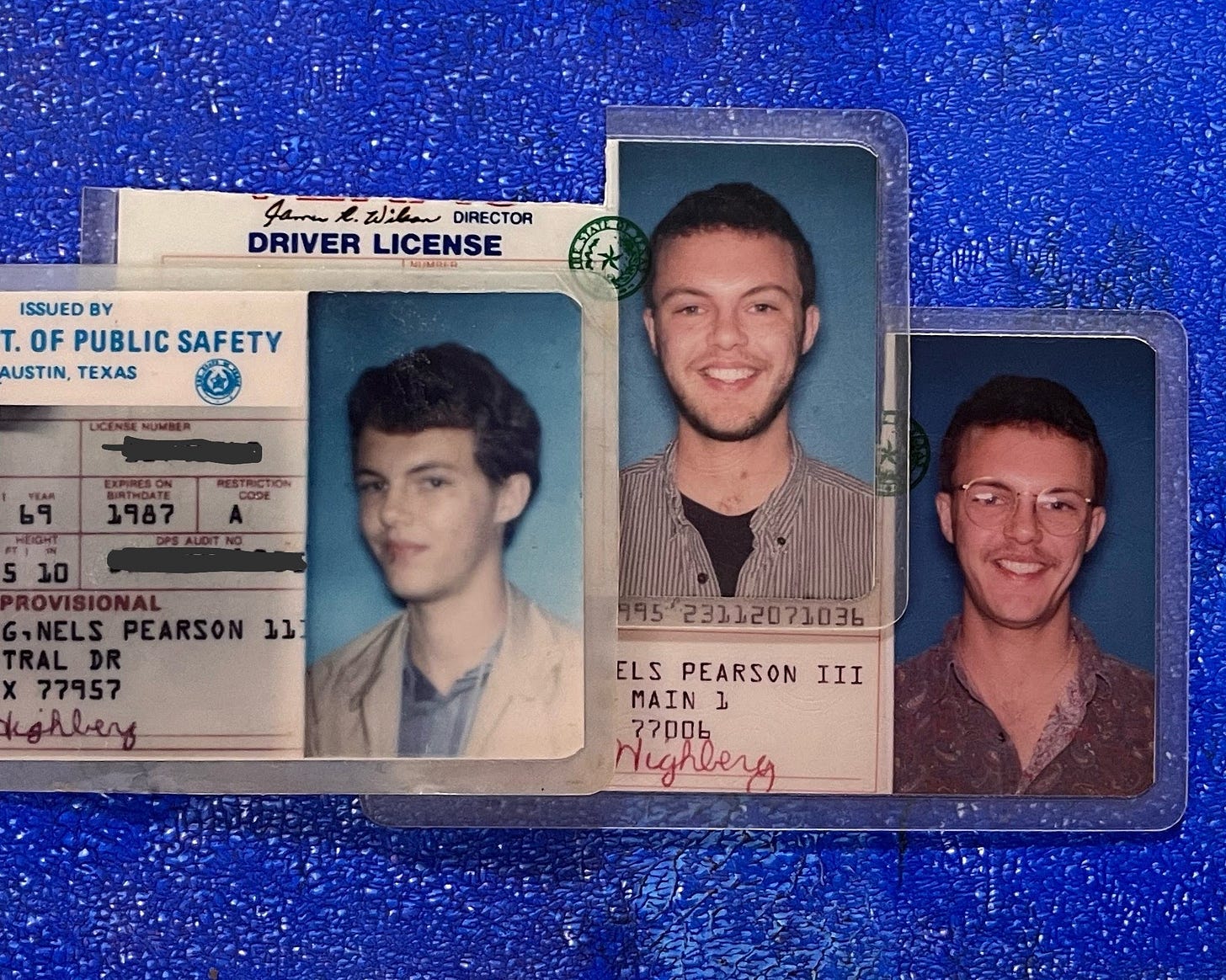

Other relics slipped in: my first driver's licenses. Three tiny cards, laminated, stiff, stamped with dates and addresses that no longer exist, photographs capturing versions of me I barely remember being. Before twenty-one, we had to turn into an almost profile (now the trend is to go vertical, I think). I love the side-eye and was so stunned to pass the driving exam that I forgot to take off my jacket. I will not discuss the beard attempt in the middle, though it is etched into memory. Spoiler alert: it got even worse. That shirt in the third was one of my favorites, my red paisley, the one I wore on Rodeo Drive, inciting a store clerk to comment, “Paisley? That’s so last year.” I felt like Julia Roberts.

Together, the jokes and the IDs, the irreverent scraps and bureaucratic records, built an unintentional archive, not just of what I did, but of how I lived, how I saw, how I laughed, how I tried to inhabit a self in a world that had not made much room for me. We didn’t save these things because we thought they were important. We saved them because, for a moment, they made us feel real.

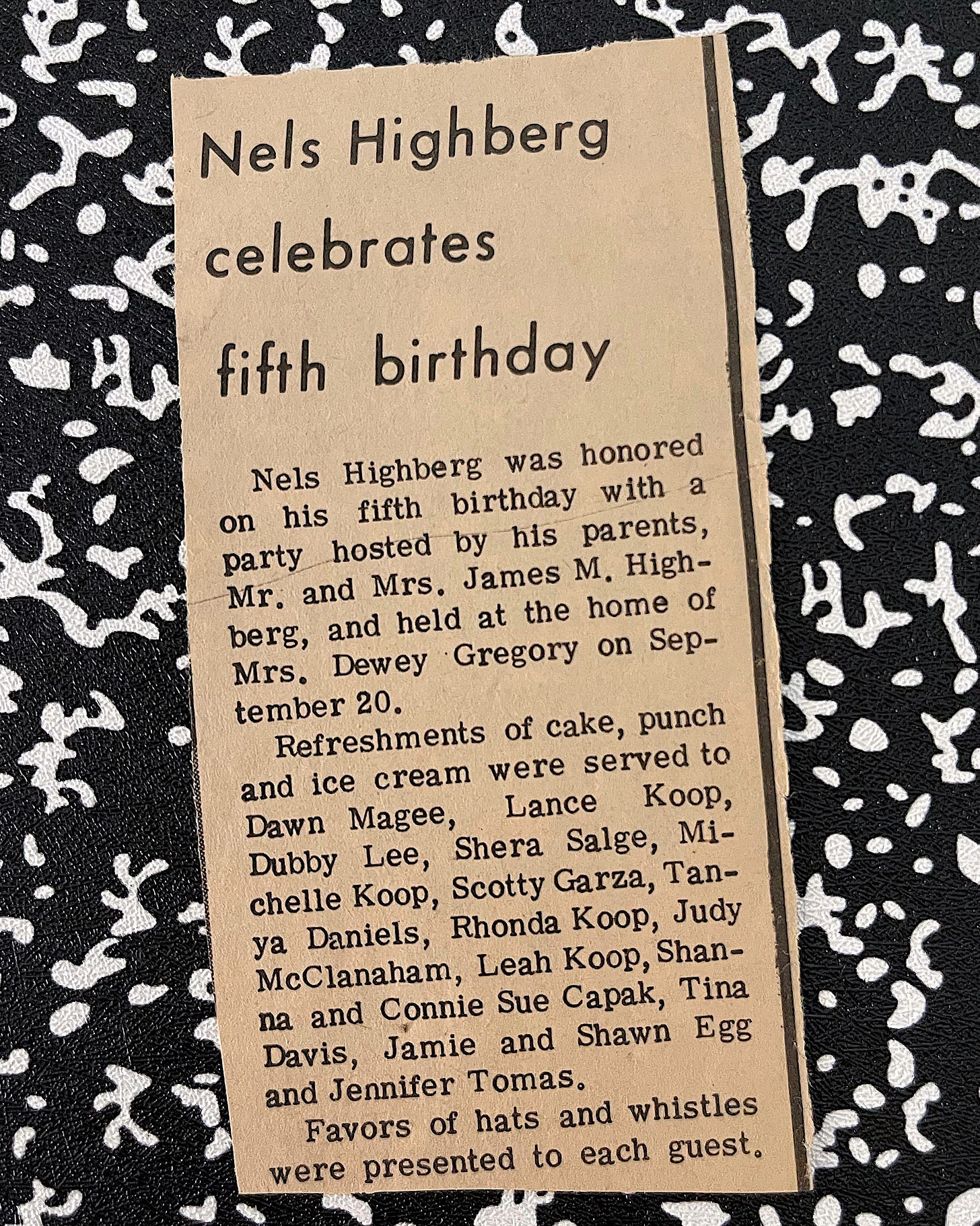

In the same envelope as the notes and cartoons, a clipping from our weekly county newspaper surfaced: a tiny article announcing my fifth birthday party, complete with a list of attendees, who each received hats and whistles. This would have been September 1974.

In small towns, the weekly paper chronicled everything: birthdays, bridge club meetings, police records, honor rolls. There was a kind of earnestness to it: the belief that everyday lives deserved recording, that community itself was a story worth telling. No moment was too small to commemorate. No gathering too minor to warrant ink.

At least for some of us. We were white and, until the divorce, middle-class. The last names of some of these kids appear on store signs and property records throughout the county to this day. Adult women were all referred to by their husbands’ names. Some of us had earned the right to be remembered and thus acquired proof of our existence.

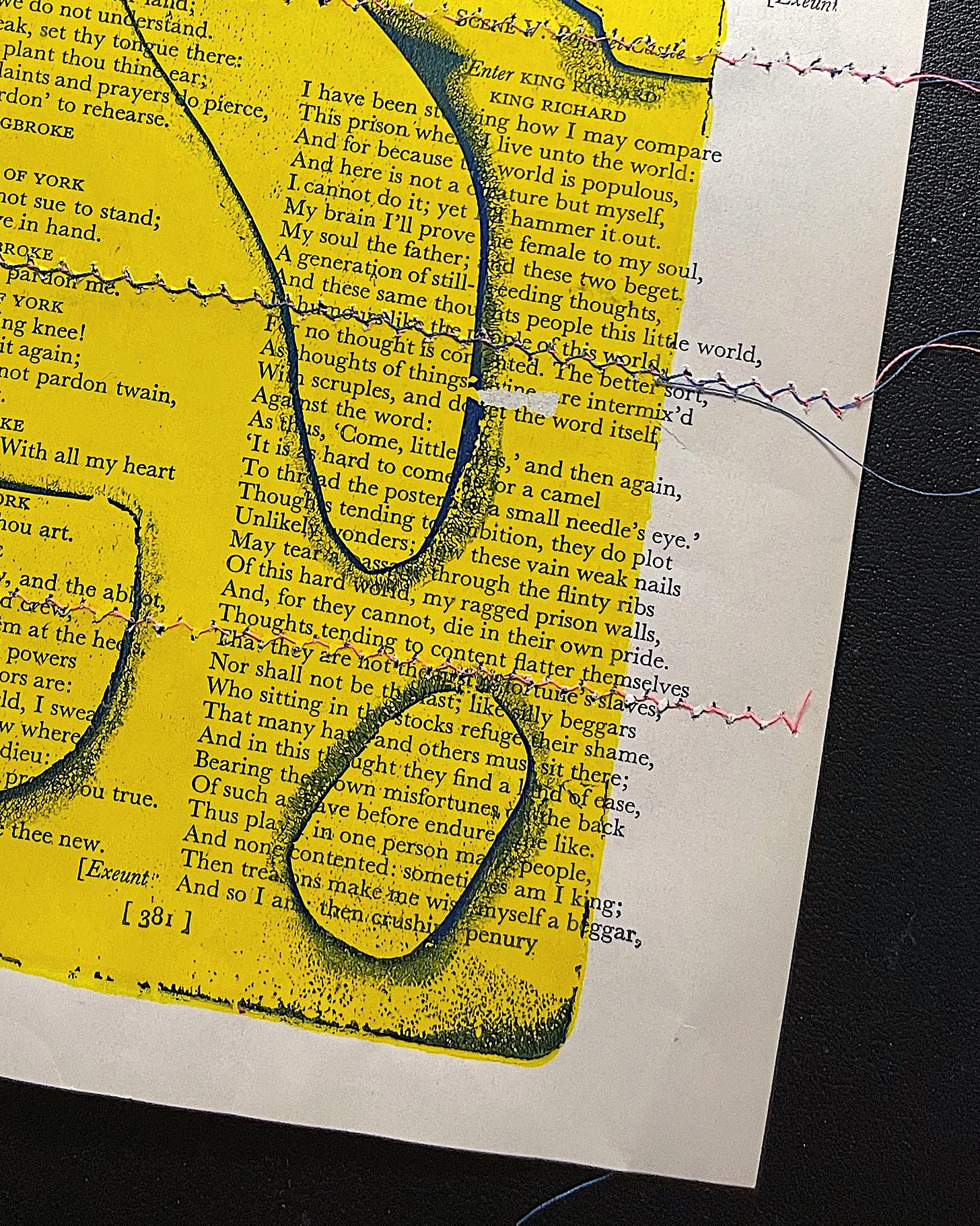

For years, I worked with the words of others in my scholarship and art: tearing pages from discarded books, manipulating scraps of paper stuck in library texts, and stitching forgotten paper into new shapes. It was safer that way, to alter what was already abandoned, to layer paint and thread over someone else’s forgotten language.

But lately, the impulse has shifted.

I find myself looking at my documents — the notes, the clippings, the IDs — and wondering what it would mean to treat them not only as artifacts but as material. Not just something to preserve, but something to transform. The writer in me knows I can scan everything and use the details, images, and memories to develop my work further. The artist has begun to wonder about printing on the originals, cutting them up, and sewing them together.

The yellow gelli print on the old page of King Richard II rehearses what I am almost ready to mount. Transparent and semi-transparent paint laid down over fragile words. Thread pulled across the surface not to close a wound, but to transform it into one that gleams and refuses erasure.

Memory isn’t a static archive; it’s a living thing. And living things must change. The scraps that tethered me to my past will tether me to something else: a future where memory isn’t just kept but transformed.

What remains are not grand gestures or polished records. What remains are the scraps: the notes folded and unfolded dozens of times, the comics torn from newspapers, the report cards celebrated as my way out of minimum wage or the military, the IDs carried for miles before ending up tucked away into drawers, the birthday clippings and honors roll announcements yellowed by decades. These fragile artifacts, saved without ceremony, have become my archive, the archive of a creator.

They carry the absurdity and tenderness of a life grown in the margins, a life marked by the ordinary things I loved enough to keep. I smile now, looking at them. They are not heavy with grief. They are light with laughter, bright with a stubborn, ordinary joy that refuses to be erased.

When HIV started killing my friends and lovers, I found it difficult to plan too far into the future. Yet a part of me must have been hoping, perhaps preparing this archive as a daydream of a time when I could look back on decades of life and appreciate that it happened.

And maybe you did, too.

What scraps have you kept, without meaning to? What might they become if you let them speak?