Tethered Four: A Lighter Kind of Memory

Cool Water, Hocus Pocus, and the Ordinary Gestures of Being Sensed

“Tethered” is a recurring series at Afraid of What They See that blends personal history, queer archives, and everyday ephemera. You can read the last post or explore the full series via this tag.

There’s a bottle of Cool Water that sits in a drawer at my boyfriends’ place. I don’t wear it most days, maybe not even most months. I only wear it in those overtly gay spaces where such markers are embraced. And I only take part in those spaces with them.

Gay men are drawn to scents, natural and synthetic, masculine and feminine alike. I’m bringing it on a gay cruise to Alaska soon, though I won’t wear it at every party; expectations for how (and if) the body will be covered vary.

I first discovered Cool Water in college, at the fragrance counter at Foley’s in Houston, where a kind saleswoman nudged me toward it, thinking it might suit me. Was that code for gay? A commission-driven push? Doesn’t matter. She was right. I wasn’t trying to be trendy. I wasn’t even trying to be noticed, not in that way. I was trying to find a scent that felt like mine: clean, light, something that didn’t lean too hard into masculinity but didn’t flee from it either.

It was the late 1980s, and the concept of “fragrance-free” didn’t exist. Brut 33 and Jovan Musk reigned among the straight boys in my hometown. GQ and Esquire were filled with cologne ads, but they felt aggressive in tone, in posture, in scent.

Now, when I open the cap on that deep blue bottle, it still smells the same: oceanic, minty, just sweet enough. It smells like the possibility of becoming someone. Like the first time a scent made me feel legible to myself, and maybe to others, too.

I remember one night in particular, how the scent lingered. Friday, July 16, 1993.

A few weeks before I left Texas for graduate school in Ohio. My tuition was paid. I had an apartment lined up in Columbus. My nervousness had become ambient noise: low-grade, constant, a hum in the background of everything. I was moving toward something good, something I had been working toward.

But I was also trying to climb out of something that kept tugging me under. I had been seeing a married urologist who was also a deacon at his Baptist church for months. He represented everything positive about being a straight, white male, things I knew I could never be, but to which I sought proximity. It wasn’t working. I needed to move hundreds of miles away because I lacked the courage to say, stop.

That night, though, none of that mattered.

July 16, 1993. I went on a date with a man whose name I can’t remember, but whose energy remains vivid. Short, bald, bearded, older than me by at least a decade, but not two, like the urologist. He was a friend of a board member at the art gallery where I worked, and he had attended my last show opening. He thought I was adorable and had been told I had a type. He was it.

He didn’t need to be the center of attention. He made rooms feel lighter. Our date wasn’t a beginning. We both knew I was leaving, and neither of us was looking for more. There was no promise, no performance. Just two men wanting to be where they were.

We tried to see Hot Shots! Part Deux, a month into its run, still somehow sold out. We ended up at Hocus Pocus, which had just opened that day. We sat in the dark of a theatre screening a family Disney film, empty on a Friday night, watching witches bicker. We didn’t know we were seeing an eventual queer classic, but we laughed. That’s what I remember most. Not the plot. Not even whether we held hands. Just the constant sound of us laughing.

Afterward, we went back to his place. Our bodies weren’t alike, and that was the point. For me, it was always the point. Touch didn’t need translation. There was nothing wild or reckless about it, but it was vivid. Present. When he leaned in close, he sniffed and smiled, kissed and touched, for a long time.

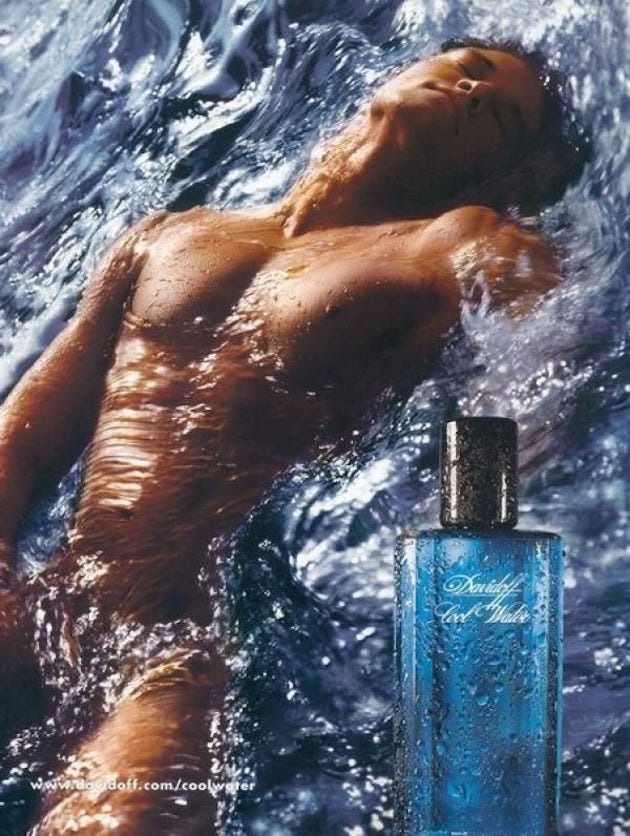

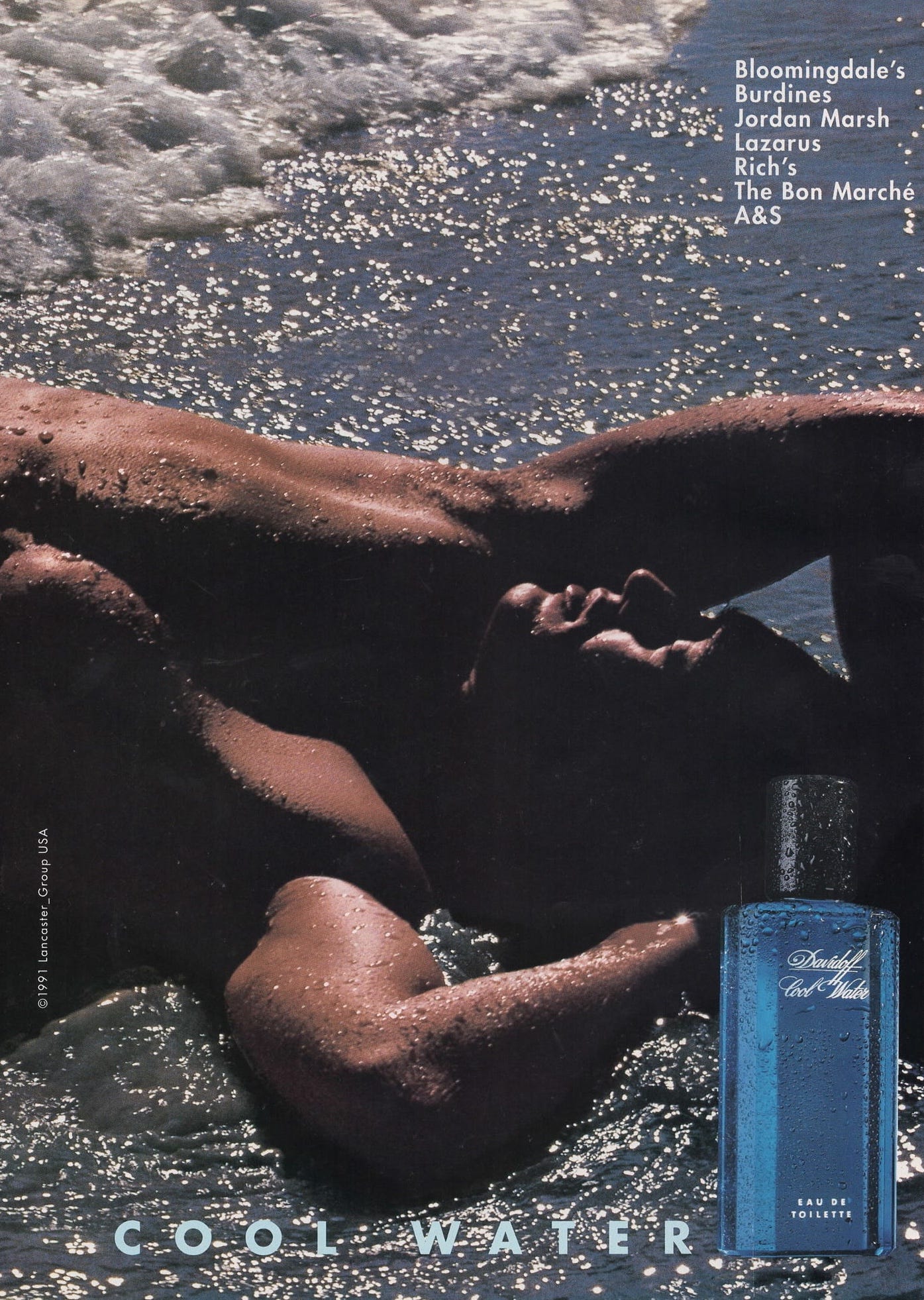

Cool Water launched in 1988, the year of my high school graduation, just a few years before that night. It was part of what was called “a new freshness,” a shift in how men were allowed to smell: cleaner, cooler, more aqueous than the heavy musk that had dominated shelves. It didn’t roar. It shimmered. Its ads, men slick with ocean water, emerging shirtless from waves, were overtly sensual but never profane. Their bodies weren’t just posed; they were part of the environment.

It had cosmopolitan origins, created by French perfumer Pierre Bourdon for the Swiss company Davidoff. They had a long history of producing cigars. Its founder, Zino Davidoff, traveled extensively through tobacco farms in South America and the Caribbean. He is credited with inventing the desktop humidor, which maintains perfect cigar humidity, similar to the natural conditions of Cuba. From that worldly history of full-bodied heaviness and substantial smoke came a crisp, breezy fragrance that left barely a sillage behind.

It offered a different kind of masculinity. Not soft, exactly, but looser. Still sculpted but less armored. No cowboys. No sports fields. No women. No aggression, just flow.

The scent stayed with me, even when I wasn’t wearing it. The bottle became part of my bedroom’s mise en scène: a deep marine blue, solid in the hand. I would sometimes pull off the cap just for a whiff, sometimes putting it on my pillow to imagine a man next to me in the dark.

When the man from that July night leaned in and smiled after an audible sniff of my torso, I don’t know what made him smile; it was either the Cool Water or the movie theatre popcorn, but he smiled. And smiled again.

Gay men have long used scent as signal, sometimes subtle, sometimes bold. I never knew a man could generate so many “natural” smells, or that they could be so fetishized. Throw in the fact that some will throw on a mist of Chanel No. 5 as an homage to their grandmother before anything traditional for men, and it’s clear why a scent, whether clove, leather, engine oil, or vetiver, someone noticed. Someone always noticed.

Cool Water wasn’t a statement, but a gesture. And gestures, as Muñoz reminds us, are where queerness often lives: ephemeral, excessive, but unmistakable.

That sniff was a moment of recognition, a kind of queer reading, a glance passed between wanderers.

He just inhaled and smiled: The smile was the basenote on which the night was written.

I don’t reach for Cool Water much anymore. It lives tucked in drawers, in travel kits, as part of rituals I perform in certain gay spaces, mostly playful and brief, where the stakes are low. The kind of night where it’s time to shimmer again.

Lightness feels rarer now. Not impossible, but endangered. Everything (grief, work, climate, memory) feels so dense, so relentless. The lightness I found that night in July wasn’t about escape. It wasn’t detachment. It was presence, before we knew being present should be a goal.

That night wasn’t dramatic. It didn’t change my life. But it was a moment I wasn’t worried about proving anything. When touch, laughter, and scent aligned. The air between us was light. My body felt light. Even my fears of leaving—and of being left—lifted.

Cool Water still smells the same. But I wear it differently now, less to seduce, more to remember.

To remind myself that the moment is still possible, like an annotation at the bottom of a page: faint, but insistent.

We don’t always know which moments will stay with us. A movie night with a film that would become beloved long after it left theaters. A scent chosen at a sales counter without strategy, merely out of hope. These aren’t grand gestures. They’re traces. But they endure.

You may have something like that, too.

A smell. A sound. A touch.

A night that made you feel more like yourself.

What scent still calls you back to the moment you felt most like yourself, not brave, not broken, just present?

Thank you — such good storytelling! I know this isn’t the main thrust of your piece but…isn’t it so weird that Hocus Pocus came out in July!? Like…what were they thinking?