“Tethered” is a recurring series at Afraid of What They See that blends personal history, queer archives, and everyday ephemera. You can read the last post or explore the full series via this tag.

I keep it near my keyboard, where my fingers sometimes find it without meaning to, playing with the worn edge, the slight indent of the lettering, the cool weight of it. On one side, it declares itself: NO CASH VALUE. On the other, an eagle framed by stars, holding something it won’t quite let go, so very American. This was never currency in the traditional sense. It has a different value, one that evolved.

I only have one. I used to carry a dozen in my pocket a night. The clerk would hand them over to us once we paid the admission to enter the back rooms, buzzed through a door to proceed down dimly lit hallways, and into shadowy booths. I discovered it a few weeks ago during the archival excavation that led to this series.

Today, when I hold it, I smile.

I smile because I was trying so hard. I was young, cautious, and bold in ways I couldn’t name. These tokens weren’t for the movies, though the films were the first time I ever saw two men kiss each other, and an adult bookstore where I kissed a man for the first time.

We had tokens in our pockets because we had to. They allowed entrance. We touched them, rolled them between our fingers, let them jingle quietly in our pockets as we stood in the dark, fingers aching to feel something.

We didn’t carry them because we liked the porn.

We carried them because we wanted each other.

The sound was small, a metallic shuffle, the kind of noise you’d miss unless it had become part of your life’s soundtrack. In the near-total darkness of those hallways, the jingle of tokens in a pocket wasn’t background; it was a signal. We didn’t talk much, certainly not at first. But the tokens spoke for us. They said: I’m here. I’m real. I’m trying, too.

We carried them like talismans, even after they’d been handed over, even when we had no intention of feeding them into the machines. Their weight in our pockets offered proof of intention, and their sound was a quiet defiance, not against the rules of the place but against the larger silence imposed on us elsewhere.

Fingers moved without thinking, rolling the coins, counting them, pressing them together. It became a rhythm, a mantra of presence. You might hear it as someone walked past, as you waited alone in a booth, or even in the brief pause before a kiss. It was a way to fill the space, to anchor ourselves in it. To say we’re doing this, even if no one outside this building ever knows it happened.

The coin in this post came from one of those very bookstores, likely when I left Houston for graduate school in 1993 or when one of them was closing. The Ballpark on West Alabama used them; The Gas Light on Holcombe did not. That’s how deeply these places rooted themselves, not only in my memory but in my geography, my rituals, and my archive of desire.

These spaces weren’t safe by any conventional standard. In lots of places, they have often been targets for raids, moral panic, and violence. The lighting was terrible. The locks were unreliable.

And still, I felt safer there than in the world outside.

Not because they were a utopia but because they were built on a kind of mutual recognition. You didn’t have to explain anything. You didn’t have to justify your presence. The boundaries were unspoken but clear: what was wanted, what wasn’t, how to decline without shame, how to walk away and still be seen.

It wasn’t erasure. It was one of the few places where my body’s desires didn’t have to be translated, hidden, or softened. They just were.

And in that stripped-down honesty, anonymous but not invisible, there was a kind of care, a type of freedom. A sort of quiet, necessary survival.

I think about it all the time, why I kept going. Why did I cross those thresholds when so many others stayed away? I didn’t try to feign heterosexuality because I never could. But not everyone lost count of their sexual partners past the first semester of college. And liked it.

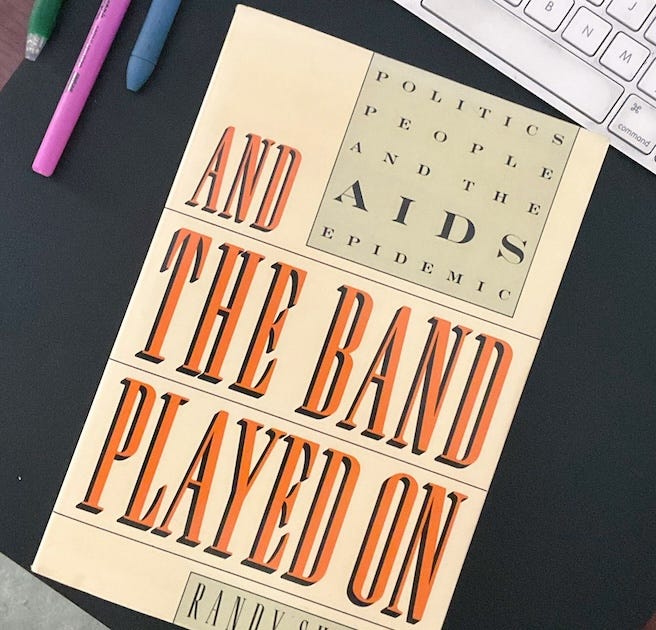

The risks were real. We knew that. Every news segment, every sermon, every nervous joke told us what could happen. And still, I went. I learned about what happened in such places because of Randy Shilts’ And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. It was a book of the month at the Quality Paperback Bookclub in my senior year. I could carry it around and read it but only get a few looks since I wasn’t the only one in speech and debate reading what was already considered one of the most important nonfiction books of our time.

Shilts saved my life. In the first academic journal article I ever published twenty years ago, I criticized the portrayal he created of Patient Zero, “The Man Who Brought AIDS to North America.” Shilts turned Gaetan Dugas into a villain and fueled a cultural narrative scapegoating gay men for our own systemic destruction.

Still, he ensured I maintained clear boundaries between what went into my body and what did not. He explained the evolution of the science surrounding HIV in ways I could understand. He also showed me where to find men like me, the businesses targeted for closure in many places. Unintended teachings but educational, nonetheless.

My body knew what it needed, not just sex, but proof that desire was still possible, not recklessly but intentionally. That I could still want and be wanted. That I hadn’t been entirely extinguished by shame or fear.

Being buzzed through that door was more than a transaction. It was a ritual. A low, mechanical acknowledgment that you belonged. That you had chosen to be recognized by a select few.

That little buzz is still in my chest when I think about those nights. A sound that became a pulse. A moment when the body stepped forward, quietly insisting on its right to touch, to feel, to refuse disappearance.

I only ever kept one. Maybe I meant to save more. Maybe I thought I had. Maybe I just liked the weight of this one best. It wasn’t until recently, the same archival excavation that unearthed old birthday clippings and new zine inspirations, that I found it again.

This coin, like so many other scraps I’ve kept, wasn’t saved because I thought it would matter. It was saved because it did matter. It marked not an event, but a threshold. A before and after.

My journals from that time are thick with longing, confusion, and the kind of specificity that only makes sense in hindsight. I knew people were dying. I felt my death was inevitable despite following all the rules. That documentation became the foundation for Diary of a Slut, a zine I described in my last post that stitches together those years with porn ephemera, handwritten memories, and scenes from the bookstores I couldn’t stop writing about.

This isn’t the first time I’ve written about those spaces. My essay, “Open 24 Hours,” in Between Certain Death and a Possible Future, tells more of that story. It’s a public examination of a long, private reckoning. Remembering has always been part of my ethos. But this coin is what tethered me to the task this time.

Maybe it was just a token. Perhaps it was just a sound, but it lingered with me: the weight in the pocket, the buzz at the door, the radio's synthpop on the speakers. These were the gestures that carried me.

I’ve always held onto things I feared disappearing, traces of my existence in case I did not survive on my own. Survival leaves traces that can become proof, a witness, or an invitation.

What gestures did you make in that time of your life that kept you tethered to yourself? What have you held onto without knowing why?

I hear the jingle still. The buzz still flutters in my chest. And in what follows, I am grateful not just for the memory but for the refusal to disappear.