Tethered Two: Annotation as Gesture, Grief as Archive

On Rafael Campo, José Esteban Muñoz, and the quiet permanence of May 15.

“Tethered” is a recurring series at Afraid of What They See that blends personal history, queer archives, and everyday ephemera. You can read the last post or explore the full series via this tag.

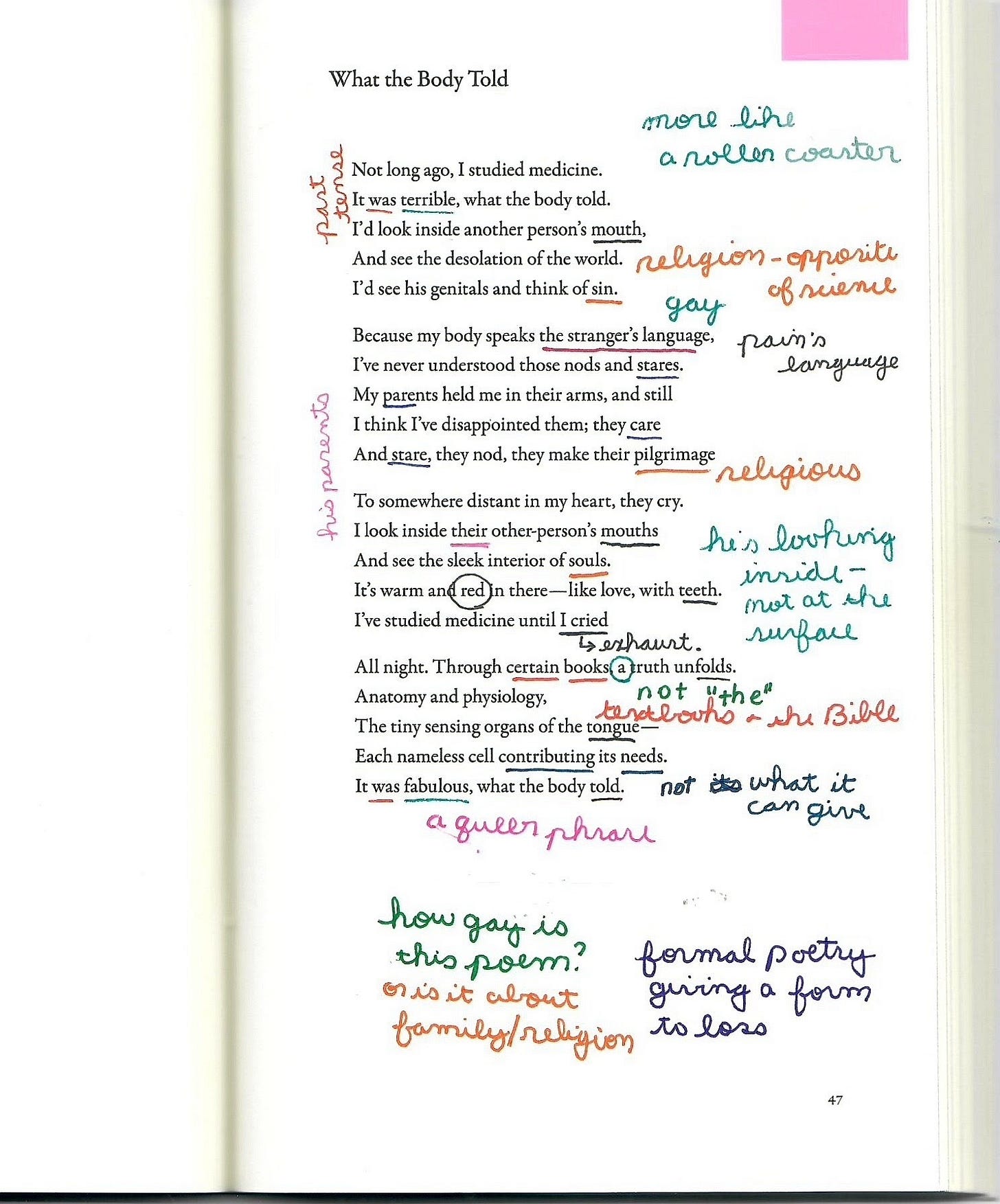

My notes aren’t color-coded with intent, not really. The pink isn’t for emotion, and the green doesn’t mean growth. The colors just mark separate thoughts—maybe even separate selves. A blue line across the margin might belong to who I was in 1998, a purple star to someone I became in 2022. These annotations span the last decade, layered over rereadings, across versions of me that flicker in and out of certainty. I return to the poem, and I leave another trace.

The poem is Rafael Campo’s “What the Body Told.” It first appeared in his 1996 collection of the same name. I was a Campo fan from the publication of his first collection, The Other Man Was Me, published two years earlier. The image is from Comfort Measures Only: New and Selected Poems, 1994-2016, the version I teach from now, though some notes were first made in the original 1996 edition. I’ve known this poem since my twenties, when I was just developing the language to talk about embodiment and knew the body had something to say, and made it a mission to figure out what it’s saying.

An annotation is not always intellectual, nor only about decoding or critiquing. It’s physical. It’s a hand moving toward a word, circling it as if to say, this one. I might need to remember this. I ask my students to annotate by hand, not to guard against AI, but because handwriting makes presence a decision. You can’t circle every word. You have to choose. You have to choose. You have to claim presence. It’s 1970s expressivist pedagogy.

There’s an intimacy in writing next to someone else’s words, especially when those words already ache with meaning. Annotation has always been more emotional than analytical for me. Typically, some form of excitement fuels each mark. Have you seen this‽ Look at this! I’m not scribbling arguments in the margins; I am making gestures.

Gestures are pivotal to José Esteban Muñoz, particularly chapter four of Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, “Gesture, Ephemera, and Queer Feeling: Approaching Kevin Aviance.” I have always been drawn to his conception of the gesture because I have loved ephemera since learning the word. I love the irony of preserving the ephemeral, which I try to do in my writing and visual art. Muñoz puts that act in queer terms.

Annotation, too, is a gesture — one made in affective excess. That’s Muñoz’s phrase for the overflow of queer feeling, a surplus that lingers. He finds it in a poem by James Schuyler, where two men share everyday intimacies that shimmer with past and present tenderness. Interestingly, a poem leads Muñoz to this understanding of the gesture, a poem he calls a “cultural touchstone” for his research: “A Photograph” by James Schulyer. The surplus in Schulyer’s poem results from “moments of queer relational bliss” in the past and present in everyday moments between two men.

Gestures allow for the creation of archives because they are relational and build on each other. They have a performative aspect (Muñoz earned tenure in performance studies) because others must recognize them. Their multilayered meanings—carrying histories of survival—reveal a utopian impulse for a queer communal future. Campo’s poem centers survival and connection, ultimately finding a resolution; it’s just not the resolution (as I note in a circle at the start of the last stanza).

I first read this poem as a graduate student in science studies. In each course of my MA, my final project focused on representations of HIV/AIDS through whatever lens we had studied. I bought every novel, book of poetry, and DVD of every film with HIV as a subject. Intellectually, it was an amazing time to be a graduate student in the humanities, working in the fertile fields of intersectional and transnational feminisms, queer studies, and critical race theories (actual CRT, not the monster). Science studies allowed for cross-disciplinary explorations within clear boundaries. My MA thesis on the gay male AIDS celebrity is still a pretty fine representation of my intellectual intents. Its interdisciplinarity still matters to me.

It’s part of what I have always loved about Campo, whom I wrote about and had done presentations on in those seminars. I did a conference presentation on doctors who wrote memoirs about treating patients with HIV, and Campo’s book of essays, A Doctor's Education in Empathy, Identity, and Poetry, was central. Then I worked with him in a Sarah Lawrence writing workshop twenty summers ago—he is as kind and attentive as his poems suggest. I’ve always loved a scientist who can speak eloquently about the soul.

I love that at some point in the past, I asked, “How gay is this poem?” I think because I initially read this as a family poem, about reconciling science with a religious upbringing he has not abandoned. He is a boy who worries about disappointing them. It is about that, and can also explain the genitals and the sins. His body speaks the stranger’s language, and in the end, as at the end, isn’t “fabulous” a (not the) right way to describe it all? What the body tells is fabulous.

Like Schuyler’s photo or my handwritten notes, gestures tether us to the past, each other, and our bodies. That’s why May 15 will always be etched in my memory. This post was always meant for May 15. I had the outline, the images, and the notes ready. But life, as always, had its annotations to add. Someone I care about was in the hospital for the last few days, a procedure that needed more recovery time before release, though all is well now. Still, irony must be noted. I am at an age where people in my generation are having to do things like go into the hospital for procedures. A lot of gay men my age note how it’s kind of amazing we arrived at this point. We’re old, and every message we received as teens was that we were going to be dead by forty.

We believed it because a lot of us were.

This collage of photos is largely from May 15, 1992, when my partner, Blane, and I had our Rite of Blessing as the local gay church called the commitment ceremonies they performed. I’ve described that night in the essay, “Open 24 Hours,” I’m so honored to have had included in Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s foundational collection, Between Certain Death and a Possible Future: Queer Writing on Growing Up with the AIDS Crisis. I also talk about that night in an essay from Catapult, “It’s More than Just ‘Two Boys Kissing’.”

May 15, 1992, was filled with gestures and affective excess. I am fifty-five years old and have lived longer than most men I have loved. For a long time, I needed to document it all and solidify the ephemeral. To a point, I feel done. I have accomplished what many writers desire when grief fuels our work: to say this person mattered to me and should not be forgotten, in the way no one should be forgotten.

I wouldn’t call it a gift, sitting in a hospital on May 15 beside someone I love. But it felt like something extraordinary, witnessing a successful procedure that was once impossible, living in a world that once felt unimaginable. Still, it is a gift that they successfully underwent a procedure that did not exist decades ago, and have access to it in ways others in my past never had. It is a different world than when I committed to Blane and Campo wrote this poem. I just received a text that my automatic monthly refill for PreP is ready. I meant to skip this month because I have a supply, but I can do that next month. I’ll take it, and I get it without paying a cent. How could I ever conceive of living in such a world?

I know Blane and all the other men would look at my life and tell me it’s fabulous. They’d be right.

What poem has stayed with you like a gesture, etched into your body’s memory, threaded through your grief, refusing to disappear?